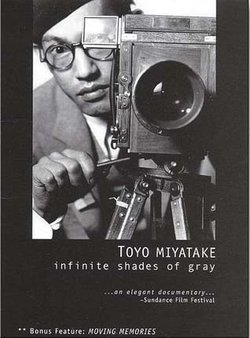

Fifteen years after its 2001 release, the award-winning documentary film Toyo Miyatake: Infinite Shades of Gray will be screened at the Japanese American National Museum on May 14. A restrained, sensitive depiction of Miyatake as a major contributor to the vital Japanese American arts scene before World War II and the effect that the war had on his life and art, the film was called “eloquent and deeply moving” by The Los Angeles Times.

Director Robert Nakamura and producer Karen Ishizuka look back on the making of the film and share their thoughts about the famous photographer of Los Angeles’s Little Tokyo as well as his documentation of Manzanar, the prison camp where he was incarcerated during the war.

* * * * *

Nancy Matsumoto (NM): What prompted you to select Toyo Miyatake as the subject of a documentary film?

Robert Nakamura (RN): Toyo Miyatake was an integral part of Japanese America in Los Angeles. While both of us were too young to have known him personally, both of our families—along with the entire JA community—were well documented

by the Toyo Miyatake Studio. First by Miyatake himself and later by his son Archie. The tradition continues to this day with family portraits and community events taken by his grandson Alan.

Karen's earliest portrait was taken by Miyatake and, as we learned later, hand-tinted by Miyatake’s wife. He also took portraits of Karen’s father and my infant brother in Manzanar. Miyatake eventually became the official photographer of Manzanar.

Karen Ishizuka (KI): My aunt Lily Okura, who was a dancer and local beauty, was one of Miyatake’s favorite models. Miyatake was especially taken with dance, a passion no doubt enhanced by his friendship and association with the great dancer Michio Ito.

My Auntie Lily recalled that other photographers would have her strike different poses to shoot, while Toyo-san would have her “just dance” as he captured her in motion.

My favorite photograph is one of my Auntie Lily lit by natural light. Always well dressed, she came to pick up some photographs from the Miyatake Studio. Toyo-san commanded her to “stay there, don’t move.” He returned with his camera and took a few shots. The result is a polished portrait that looks like it was set up in the studio. The clue that it wasn’t is that her car keys are still her hand.

NM: As you researched and wrote the film, what surprised you most about Toyo Miyatake?

RN: Because we had known him as the ultimate community photographer, we were amazed to discover what a fine and well-exhibited pictorial photographer he was. His art photography was highly nuanced, often abstract, and totally contemporary with other pictorialists of the time. He knew Edward Weston, whom he actually helped early in Weston’s career—organizing one of his first exhibitions and buying his then-unknown photographs. One of them, featured in the film, had been marked down from something like five dollars to four dollars.

NM: The film touches briefly on the various reasons why Miyatake stopped doing art photography after the war. Do you wish he had continued, or do you feel that the times had changed and it wasn’t possible for him to do so?

RN: Both. Personally, I wish he

would have continued, since he was such a talented artist. But the war changed everything—not only for Miyatake, but for all Japanese Americans. Life was forever dichotomized into “before the war” and “after the war.” Already accomplished, who knows how far he could have gone.

KI: Yet that is also the case for everyone whose careers were cut short. So in that sense, the war and camps were tragic. But I don’t think of Miyatake’s life as tragic and I don’t think he would either. Because he was an artist—whether well-known or not, so-called “successful” or not, whether anyone else knew it or not. He made art all his life, whether it was capturing my Auntie Lily with her car keys, or documenting the ineffable joys of family milestones.

NM: The vast majority of JA families who had their pictures taken by Miyatake were probably not aware of what a skilled fine art photographer he was. Do you think he cared about that? Or was he just happy to be thought of as Little Tokyo’s photographer?

RN: Very few people, even his personal friends and certainly not the hundreds of JA families that frequented his studio, knew about his pictorial work before seeing the film. Many people who knew him well told us that. To our knowledge, he didn’t regret or even dwell in the past. He was too busy living in the present. For example, he carried his camera with him wherever he went. So it’s not that his art was confined to the commercial studio or that he only thought of himself as Little Tokyo’s photographer. He was a photographer through and through.

NM: The film starts with an interview with Hirokazu Kosaka, the artist and Buddhist priest, who discusses the concept of engawa (veranda, porch) and shades of gray. Why did you decide to make this the title of the film?

RN: Two reasons. First, Miyatake worked in black and white. In photography there is what is called a grayscale—a range of shades of gray, which is without color. The darkest shade of gray is black and the lightest is white.

Second, Miyatake’s sense of aethetics was so fine that one could say he worked in the realm of infinite shades of gray. In Western culture, there is much definition and hence separation, with little room for nuance and subtlety; things are either black or white. In Japanese aesthetics, everything is nuanced and subtleties are not only seen but admired. Miyatake understood not only the shades of gray in between black and white, but the infinite shades of gray.

KI: You asked about the engawa, which is something Hirokazu brought up to help explain the nuance in Japanese aesthetics. The engawa is a veranda that surrounds a traditional Japanese house. As an integral part of the house that lies just outside on its perimeter, the engawa is neither inside nor outside. It is the space between inside and outside. Again, Hirokazu was alluding to the fine distinction that Miyatake was able to attain in his art.

NM: Kosaka also explains in the film that in Japan there is no separation between time and space. Then he segues into a description of a mosquito bumping up against a shoji screen. How does this reflect Miyatake’s aesthetic?

KI: When Hirokazu evoked the sound of a mosquito hitting a shoji screen—a sound most people would not even hear much less take notice of—he was alluding to the fine appreciation for subtlety and aesthetics that Miyatake possessed. In Buddhism there is no separation between time and space.

RN: Miyatake’s understanding of this is evidenced in his photograph of a dancer that looks like a blur. You can’t even see the dancer, only the condensation of time and space. Keeping the lens of his camera open for longer than the usual amount of time, he literally fused time and space, transposing the body of a dancer into pure motion.

NM: How do you feel about Infinite Shades of Gray when you look at it today, 15 years after it was made?

RN: Often, with the external constraints of time and money, you have to complete a film that you wished you could have done more with. This past January, the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens in Florida screened the film and we have to admit, seeing it for the first time in a long time, we were actually quite pleased. Not only was it received well by a non-Asian audience, we personally were very gratified by it.

KI: We had the full support of Toyo’s son Archie Miyatake who, in the process of our research, actually found gems he didn’t know he had, like Toyo-san’s home movies and the Weston prints. We were fortunate to be able to interview people who knew him well, like Hirokazu, who was a young artist at the time; my Auntie Lily, whom he loved to photograph; and of course, his son Archie, who carried on the studio. We interviewed curators Dennis Reed and Karin Higa, who both did a lot of research on Toyo’s pictorial work and were instrumental in helping us—and the viewer—understand the importance of his art. And we had the good fortune of having a great crew; John Esaki’s cinematography was impeccable, and David Iwataki’s music score greatly enhanced the film’s imagery.

RN: Inspired by Miyatake’s aesthetics, we made what other documentary filmmakers might consider a bold aesthetic choice by including long, lingering shots of the photographs themselves with little voiceover or other explanation. We wanted to give the viewer the opportunity to really see and appreciate these little-known photographs, knowing how special and rare they are.

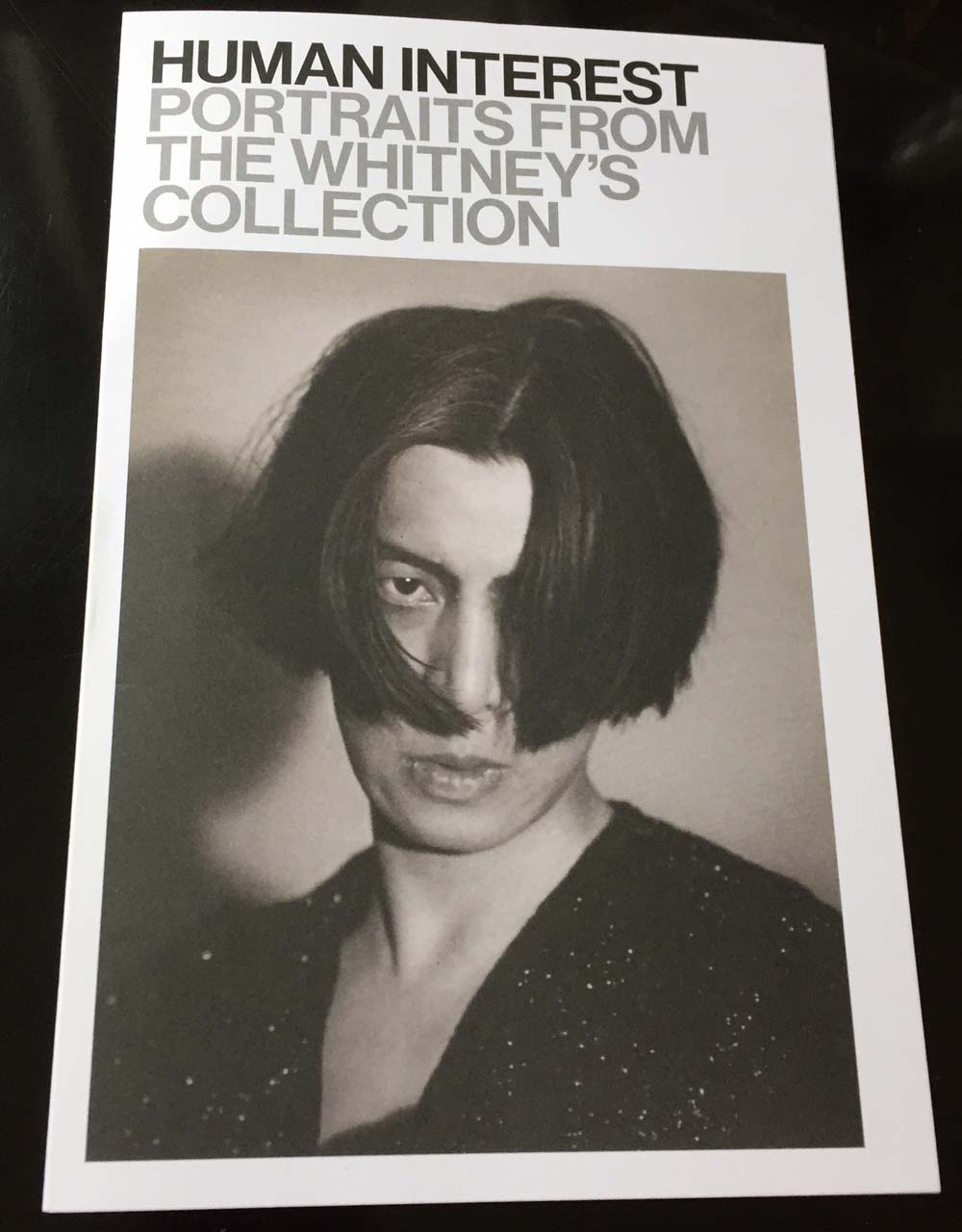

Miyatake's portrait of dancer Michio Ito is included in the Whitney Museum's

current exhibition, "Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney's Collection.

NM: It came as a shock to me to realize that it is Miyatake's portrait of Michio Ito gracing the cover of an invitation to the Whitney Museum's current exhibition, "Human Interest: Portraits from The Whitney's Collection." The New York Times, in a review of the show, noted that the portrait "gains particular intensity when it is remembered that Ito, who had a successful career in the United States, would be arrested within 24 hours of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, falsely accused of espionage, and interned for two years before being shipped back to Japan." What is your reaction to this timely appreance of Miytake's work in a very large mainstream art exhibit, and the way it was covered in this review?

KI: They use a cropped version of Miyatake’s original portrait that included Ito’s hands delicately crossed in front of him. This full image—with hands almost in dance—makes the photograph even more dramatic—and is one of my favorite Miyatake portraits. Not only does it capture Ito’s theatricality, the portrait exudes an androgenous masculinity and sexuality that the musician Prince became famously known for decades later. It is this—Miyatake’s impeccable eye that not only captured Ito’s beauty but simultaneously refuted ridiculous visual stereotypes of Asian men—more than the fact that Ito was incarcerated—that gives the portrait such intensity.